Last Updated on February 18, 2026

Accelerating the Development and Adoption of Biomarkers

A key component needed in the fight against preeclampsia is the development of tests for simple, rapid, and accurate diagnosis and prediction.

The Preeclampsia Foundation has advocated for the development and adoption of biomarkers and improved testing for preeclampsia for over a decade by bringing together leaders in research, industry, regulatory bodies, policy makers, professional societies, and eventually payers to engage and address this call to action, remove barriers and accelerate the development and adoption of biomarkers to improve screening and diagnosis of hypertensive and placental disorders of pregnancy.

What are biomarkers?

Biomarkers are powerful laboratory tools that can be used to detect or predict illness before symptoms begin. They are often measured from a person's blood, bodily fluids, or tissues. These unique biological products are found throughout the body. Blood pressure, urine tests, and blood work are a few biomarkers that give healthcare providers information about pregnancy health. The research into preeclampsia biomarkers has found that pregnant patients who go on to develop preeclampsia have different levels of certain biomarkers. Some relate to the growth of the placenta, some related to the body's reaction to inflammation, and some may even be genetic.(Watch our video about preeclampsia testing)

There are several important benefits to introducing biomarkers and better testing into the fight against preeclampsia:

- Screening pregnant women during the first and second trimester for pre-symptomatic disease to enable interventional research studies, accelerating progress toward a cure;

- Determining disease severity and risk stratifying women to improve disease management, such as timing of delivery;

- Reducing costs associated with short and long term medical care by eliminating unnecessary testing and surveillance[i];

- Most importantly, saving the lives and well-being of mothers and their babies.

Which biomarkers are relevant to the diagnosis of preeclampsia?

Clinically relevant biomarkers of preeclampsia can be divided into placental, inflammatory, endothelial and metabolic categories[i]. A few promising biomarkers include Placenta Growth Factor (PlGF) which is involved in the modulation of the placental and maternal vascular system[ii], soluble FMS-like tyrosine kinase-1 receptor (sFlt-1) which antagonizes blood vessel formation and promotes endothelial dysfunction[iii], asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), which interferes with nitric oxide production and leads to abnormal vascular function[iv], Congo Red, a test of protein-folding abnormalities in the urine of preeclamptic women[v], RNA signatures, and others. Combined with usual clinical and ultrasound surveillance during pregnancy, these biomarkers have been shown to diagnose preeclampsia and predict adverse outcomes with an even greater accuracy than traditional tests[vi],[vii], and some have even been shown to reduce medical costs associated with evaluations of suspected preeclampsia[viii].

Where is the FDA on the use of biomarkers?

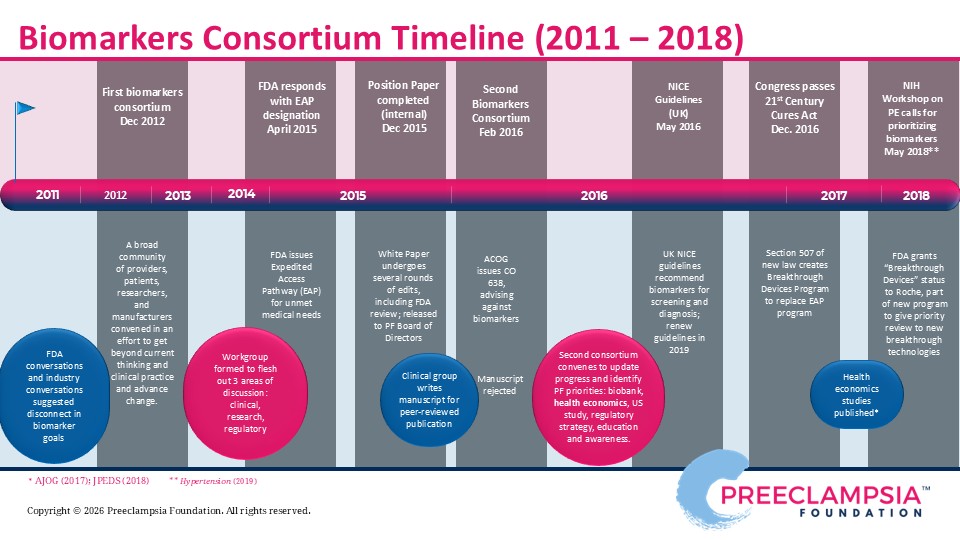

Efforts to bridge the gap between biomarker research and widespread clinical use led to the Preeclampsia Foundation hosting two biomarker consortia, in 2012 and 2016. An interdisciplinary team of experts convened to debate the current state of the biomarker field, present challenges, such as regulatory hurdles, define the need through both clinical and patient perspectives, and develop recommendations to move forward. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which regulates most diagnostic tools like biomarkers, participated in our meeting. Detailed findings of the consortia proceedings are summarized in our 2012 Report to Stakeholders and our 2016 Meeting Proceedings. As a result of these dynamic conversations, the FDA recognized some tests may provide substantial improvement over currently available clinical and diagnostic testing to diagnose preeclampsia and, hence, made an expedited review and approval process available to manufacturers pursuing commercial development.

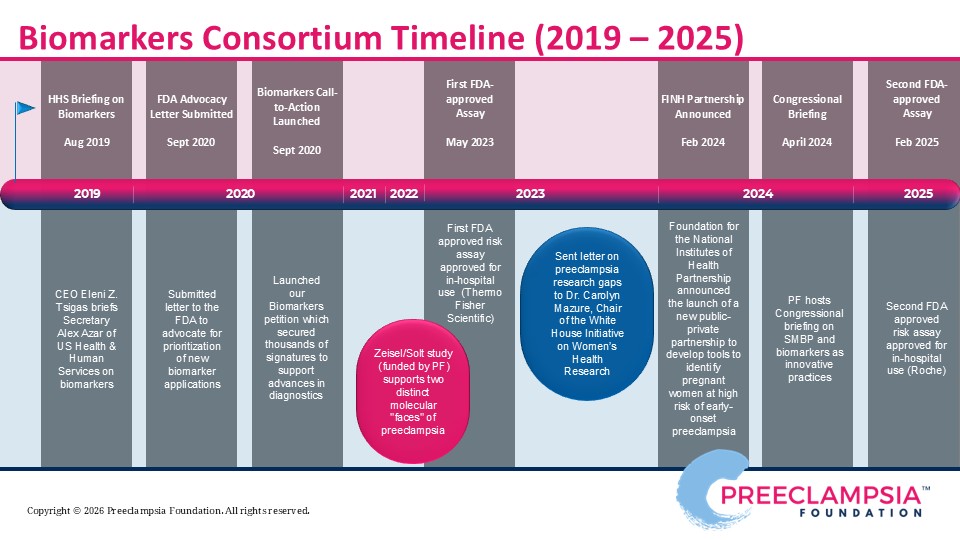

In 2023, the first-ever FDA-approved test for preeclampsia was approved, which measured Placental Growth Factor (PlGF) plus and soluble FMS-like tyrosine kinase-1 receptor (sFlt-1) via a blood serum test to aid in clinical management of preeclampsia. The intended use of the test is for hospitalized patients between 23 and 35 weeks' gestation with either diagnosis of a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy or a suspicion of preeclampsia. This is a prognostic test for risk stratification, to help obstetricians determine what patient may need immediate intervention, and what patients may benefit from continued close monitoring. Another FDA-approved test for the PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio was launched in 2025.

Biomarkers are said to be the first major step in the U.S. to really help our obstetricians and clinical colleagues identify groups of patients who are at high risk for adverse outcomes and differentiate them from patients who are at low risk for adverse outcomes. Those with lower risk can potentially prolong pregnancy, thereby reducing planned prematurity that comes with preterm delivery that is often needed with the strong suspicion of severe preeclampsia.

Read our 2019 preeclampsia biomarkers petition

REFERENCES

[i] O'Gorman N (2016). Competing risks model in screening for preeclampsia by maternal factors and biomarkers at 11-13 weeks gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 214:103 e101-103 e112.

[ii] Shih T (2016). The Rising Burden of Preeclampsia in the United States Impacts Both Maternal and Child Health. Am J Perinatol, 33:329-338.

[iii] English F (2015). Risk factors and effective management of preeclampsia. Integr Blood Press Control. 2015; 8: 7–12.

[iv] Stevens W (2017). Short-term costs of preeclampsia in the United States health care system. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 217:237-248 e216.

[v] Hao J (2019). Maternal and Infant Health Care Costs Related to Preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol, 1227-1233.

[vi] Ananth CV (2013). Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980-2010: age-period-cohort analysis. BMJ, Nov 7;347:f6564.

[vii] Johnson JD (2020). Does race or ethnicity play a role in the origin, pathophysiology, and outcomes of preeclampsia? An expert review of the literature [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 24]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;S0002-9378(20)30769-9.

[viii] Tucker MJ (2007) Black-White disparity in pregnancy-related mortality from 5 conditions. Am J Public Health. 2007; 97:247-251.

[ix] Webster J (1903). A Text-Book of Obstetrics. Philadelphia: Saunders.

[x] Li R (2017). Health and economic burden of preeclampsia: no time for complacency. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 217:235-236.

[xi] Schnettler WT (2013). Cost and resource implications with serum angiogenic factor estimation in the triage of pre-eclampsia . BJOG, Sep;120(10):1224-32.

[xii] Eastabrook G (2018). Preeclampsia Biomarkers: An assessment of maternal cardiometabolic health. Pregnancy Hypertens, 13:204-213.

[xiii] Chau K (2017). Placental growth factor and pre-eclampsia. J Hum Hypertens, 31:782-786.

[xiv] Maynard SE (2003). Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest, 111:649-658.

[xv] Yuan J (2017). Circulating asymmetric dumethylarginine and the risk of preeclampsia: a meta-analysis based on 1338 participants. Oncotarget, 8:43944-43952.

[xvi] Rood KM (2019). Congo Red Dot Paper Test for Antenatal Triage and Rapid Identification of Preeclampsia. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;8:47-56.

[xvii] Duhig KE (2019). Placental growth factor testing for suspected pre‐eclampsia: a cost‐effectiveness analysis. BJOG, Oct;126(11):1390-1398.

[xviii] Barton JR (2020). PETRA Trial. Placental growth factor predicts time of delivery in women with signs or symptoms of early preterm preeclampsia: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol, Mar;222(3):259.e1-259.e11.

[xix] Duckworth S (2016). Placental Growth Factor (PlGF) in Women with Suspected Pre-Eclampsia Prior to 35 Weeks' Gestation: A Budget Impact Analysis. PLoS One, Oct 14;11(10):e0164276.

[xx] O'Gorman N (2017). Accuracy of competing-risks model in screening for pre-eclampsia by maternal factors and biomarkers at 11-13 weeks' gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, June;49(6):752-755. Erratum in: Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Dec;50(6):807.

[xxi] Zeisler H (2016). Predictive Value of the sFlt-1:PlGF Ratio in Women with Suspected Preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):13-22.

[xxii] Cerdeira AS (2019). Randomized Interventional Study on Prediction of Preeclampsia/Eclampsia in Women With Suspected Preeclampsia: INSPIRE. Hypertension. 2019;74(4):983-990.

[xxiii] NICE (2016). PlGF-based testing to help diagnose suspected pre-eclampsia (Triage PlGF test, Elecsys immunoassay sFlt-1/PlGF ratio, DELFIA Xpress PlGF 1-2-3 test, and BRAHMS sFlt-1 Kryptor/BRAHMS PlGF plus Kryptor PE ratio). Retrieved from National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg23

This educational resource covers the clinical background, pathophysiology, and use case for ratio tests on two key placental protein markers, sFLT-1 and PLGF related to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in the United States. (For global use and evidence, see the appendix.)

Appendices deck includes additional slides on...

- Praecis at Roche study

- Global perspectives and impact

- Patient views on predictive and diagnostic tests

Materials are meant for educational and informational purposes and may be downloaded, used, and shared in full or in part for such purposes. Please do not alter or edit individual slide content without express written permission from the Preeclampsia Foundation.

Related Articles

Congratulations on receiving your brand new Cuff Kit®! Want to learn more about how to use your iHealth Track device? Here are some handy videos and links to get you started. Unpacking and using...

Nurses play a vital role in detecting preeclampsia and caring for patient before, during, and beyond pregnancy.

Preeclampsia can strike quickly. Give new and expectant moms the best tool for early detection of hypertensive disorders with the Preeclampsia Foundation Cuff Kit® - a pregnancy-validated monitor wit...

Every woman should be able to check her own blood pressure at home.

Order our Ask About Aspirin Rack Card. Aspirin can prevent the formation of blood clots. This can make aspirin useful in treating or preventing some conditions like heart attacks and st...

Preventing and managing high blood pressure with healthy lifestyle behaviors are at the center of updated clinical guidelines published this week in the American Heart Association (AHA) peer-reviewed...

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are a leading cause of maternal death in the state of Indiana. To address this critical issue, the Indiana Hospital Association is teaming up with the Preeclampsia...

Recientemente, me encontré con una publicación en las redes sociales señalando la crisis de salud maternal desde la perspectiva de una mujer negra. Una persona respondió a...

For more on the Preeclampsia Foundation's work to amplify all research related to biomarkers for improved prediction and diagnostic tools, please visit https://preeclampsia.org/biomarkers. INDIANAPOL...

GAP—SPIRIN campaign gets low-dose aspirin to those most at risk to help close the maternal health gap in preeclampsia ________ NEW YORK, January 23, 2025/PRNewswire/ – In recognition of...