What are the risk factors for preeclampsia? An updated research perspective

What you’ll learn in this article:

- Many risk factors contribute to an individual’s chance of getting preeclampsia. These risk factors may be genetic, physical, environmental, and even social.

- Don’t blame yourself for developing preeclampsia: there’s currently no absolute way to prevent it from happening.

- “Risk reduction” doesn’t equal “disease prevention.” There are actions you can take (and should, if possible!) to lower your risk of getting preeclampsia, but there’s still no guarantee you won’t get it.

- Understanding individual risk factors can help patients have constructive pre-conception or early prenatal conversations with their providers.

Researchers study lots of different risk factors to see how they affect your chance of developing preeclampsia.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy occur in about 5-8% of pregnancies worldwide, or about 1 in every 20 pregnancies. This is the general population risk. This number is found by looking at large numbers of pregnant patients and counting how often preeclampsia occurs.

Some patients may be more likely to get preeclampsia because of certain risk factors. The more risk factors that you have, the higher your chance of developing preeclampsia during pregnancy. This is known as individual risk – or in other words, your unique, individual likelihood of developing preeclampsia. (See our article on Understanding Risk for more on the difference between population and individual risk.)

Some risk factors are things that patients can possibly change like weight, blood sugar, or blood pressure prior to pregnancy. Others, like family history or ethnicity, cannot be changed. Unfortunately, even patients with no risk factors may still develop preeclampsia.

A recent panel of research experts conducted a large study published in BJOG International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology to look at 78 different risk factors that have been reported to contribute to the chance of getting preeclampsia. These factors came from clinical practice guidelines from 17 obstetric organizations from around the globe (like the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology here in the United States or the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada).

The 78 risk factors at which the panel looked are regularly quoted by other organizations (including us) as the main risk factors for preeclampsia. But the researchers wondered: “are these risk factors truly related to preeclampsia? And if so, how likely is a patient who has one or more of these risk factors to develop preeclampsia? What does the research evidence tell us about each?”

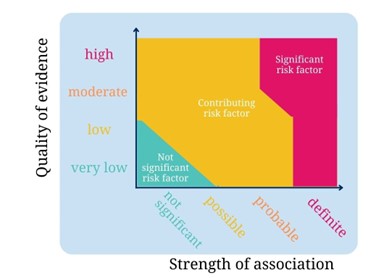

The panel looked at the evidence behind each of these risk factors to find out two things:

- the “quality of evidence”: or in other words, how well-done and strong the research on that specific risk factor was. This was ranked by four categories: high, moderate, low, and very low.

- the “strength of association”: or in other words, how much that risk factor actually contributed to an individual patient’s likelihood of developing preeclampsia. This was ranked by four categories: definite, probable, possible, not significant.

That means that risk factors with “high” quality of evidence and “definite” strength of association have the highest impact on a patient’s chance of developing preeclampsia. “Probable” strength of association means that this risk factor is still very likely to contribute to your chance of developing preeclampsia. Risk factors with “very low” quality of evidence and “not significant” strength of association are therefore the least likely to affect the general population’s risk of developing preeclampsia.

A few key findings arose from the study:

- Obesity (defined as a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2) was the only risk factor that had a “definite” association with preeclampsia based on “high” quality evidence. Overall, weight and blood sugar issues seemed to have the highest relationship to overall risk of preeclampsia.

- Many risk factors fell into the “probable” association with preeclampsia. Key factors like maternal age, going into pregnancy with high or somewhat high blood pressure readings, certain ethnicities, and chronic health conditions made up the majority of this “probable” group.

- The study identified a few new risk factors that had “definite” or “probable” associations with preeclampsia, including severe anemia, being pre-hypertensive, and having had a prior stillbirth. These risk factors may be added to clinical care guidelines in the future.

- Few risk factors had “high” or “moderate” quality of evidence. This speaks to the continuing need for more research on the relationship between individual risk factors and preeclampsia. (Learn more about how patients can share their experiences to further research through the Preeclampsia Registry.)

Below are all the risk factors that the study examined.

|

Risk Factor |

Scale |

|

|

Strength of association |

Quality of evidence |

|

|

Demographics |

||

|

Maternal age |

||

|

Adolescence |

Definite |

Low |

|

Advanced maternal age (>40 yrs) |

Probable |

Low |

|

Ethnicity |

||

|

African-American |

Probable |

Very low |

|

Sub-Saharan African |

Probable |

Low |

|

South Asian |

Probable |

Low |

|

Pacific Islander |

Possible |

Low |

|

Maori |

Probable |

Low |

|

Low socioeconomic status |

Possible |

Very low |

|

Past Medical History |

||

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

||

|

Obesity (BMI≥30) |

Definite |

High |

|

Overweight (BMI 25-29.9) |

Probable |

High |

|

Chronic hypertension |

Definite |

Moderate |

|

Pregestational diabetes |

||

|

Type 2 |

Definite |

Moderate |

|

Type 1 |

Definite |

Low |

|

Anemia |

||

|

Severe anemia |

Definite |

Low |

|

Anemia |

Probable |

Low |

|

Sickle cell disease |

Probable |

Low |

|

Thalassemia |

Not significant |

Very low |

|

Obstructive sleep apnea |

Probable |

Moderate |

|

Autoimmune diseases |

||

|

Antiphospholipid syndrome |

Probable |

Moderate |

|

Systemic lupus erythematosus |

Probable |

Low |

|

Rheumatoid arthritis |

Probable |

Low |

|

Chronic kidney disease |

Probable |

Low |

|

Polycystic ovary syndrome |

Probable |

Low |

|

Thrombophilia |

Probable |

Low |

|

Infections |

||

|

Periodontal disease |

Probable |

Low |

|

Helicobacter pylori infection |

Probable |

Low |

|

Hepatitis B infection |

Possible |

Low |

|

HIV |

Not significant |

Very low |

|

Tuberculosis |

Not significant |

Very low |

|

Mental health |

||

|

Depression |

Probable |

Low |

|

Stress |

Possible |

Very low |

|

Anxiety |

Not significant |

Very low |

|

Lower maternal birthweight or preterm delivery |

Possible |

Low |

|

Past Obstetric History |

||

|

Prior preeclampsia |

Definite |

Moderate |

|

Prior stillbirth |

Probable |

Moderate |

|

Prior abruption |

Probable |

Low |

|

Prior pre-term birth |

Probable |

Low |

|

Prior HDP |

Possible |

Low |

|

Endometriosis |

Possible |

Very low |

|

Prior SGA or low birthweight |

Not significant |

Very low |

|

Prior miscarriage |

||

|

At ≤10 weeks with same partner |

Probable |

Low |

|

Recurrent |

Probable |

Very low |

|

Timing and number unspecified |

Possible |

Low |

|

Family History |

||

|

Preeclampsia |

||

|

In mom or sister |

Probable |

Moderate |

|

In father of baby |

Possible |

Very low |

|

Unspecified family member |

Probable |

Low |

|

Cardiovascular disease (of family member) |

Probable |

Low |

|

Current Pregnancy |

||

|

Trisomies |

||

|

Trisomy 13 |

Definite |

Moderate |

|

Trisomy 21 |

Probable (decreased risk) |

Very low |

|

Trisomy 18 |

Not significant |

Very low |

|

Smoking |

Probable (decreased risk) |

Moderate |

|

First pregnancy (nulliparity) |

Probable |

Low |

|

Early pregnancy BP |

||

|

sBP 120-129 (with dBP <80) |

Probable |

High |

|

sBP ≥130 or dBP ≥80mmHg |

Probable |

High |

|

Abnormal uterine artery Doppler |

Possible |

Low |

|

Infection (any) |

Probable |

Moderate |

|

Urinary tract infection |

Possible |

Moderate |

|

Malaria |

Not significant |

Very low |

|

Multiple pregnancy (twins, triplets, etc.) |

Probable |

Low |

|

Excessive weight gain in pregnancy |

Probable |

Low |

|

Gestational diabetes |

Probable |

Low |

|

Barrier contraception |

Probable |

Low |

|

New or change in partner |

Probable |

Low |

|

Duration sexual relationship <12 months with current partner |

Possible |

Very low |

|

Artificial reproductive technology (includes IVF, sperm donation, egg donation) |

Probable |

Very low |

|

Interpregnancy interval ≥10 yrs |

Possible |

Very low |

|

Vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy |

Not significant |

Very low |

So what does this mean for you as a person who survived preeclampsia or HELLP syndrome?

If you are planning to have another pregnancy, forewarned is forearmed. Your previous experience with preeclampsia is a definite risk factor for preeclampsia. Make a pre-conception appointment with a maternal-fetal medicine specialist to go over your previous pregnancy. Ask them about any actions you can take prior to or during your next pregnancy (such as taking low dose aspirin) that may help decrease your risk. Modify the risk factors that you can control, such as controlling continuing high blood pressure through medication or lifestyle modifications. (Read more about Another Pregnancy After Preeclampsia.)

Related Articles

Ánimo y cuídate: la preeclampsia puede estar asociada con enfermedades cardíacas y accidentes cerebrovasculares más adelante en la vida Descargue nuestra hoja informativa

Eclampsia is a very serious complication of preeclampsia characterized by one or more seizures during pregnancy or in the postpartum period.

Your story is needed to improve outcomes for moms like you. Add your voice to critical preeclampsia research to ensure that every story is heard.

La preeclampsia, en todas sus formas, puede requerir muchos análisis, tanto durante como después del embarazo. ¿Alguna vez se preguntó por qué el proveedor de atención médica le solicita tantos anális...

Recent findings in preeclampsia research have shown that preeclampsia likely has at least two variants – an early onset and a late onset variant. Early onset is typically defined as before 34 we...

Preeclampsia is a pregnancy complication marked by new-onset high blood pressure and signs of stress on organs such as the kidneys, liver, and brain. While much attention is often given to preterm dis...

Preeclampsia is a serious problem that can happen during pregnancy. It often affects the brain and can cause headaches, vision problems, strong reflexes, and seizures (called eclampsia). In this study...

Pregnancy offers a unique window into a woman’s future heart and cardiovascular health. Conditions such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) which include gestational hypertension, preec...

Heart disease, also called cardiovascular disease (CVD), is becoming more common in young women across the United States. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) is a group of conditions that includ...