Last Updated on August 08, 2025

Postpartum Preeclampsia: Moms are Still at Risk After Delivery

Most women with preeclampsia will deliver healthy babies and fully recover. However, some women will experience complications, several of which may be life-threatening. A woman’s condition can progress to severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, or HELLP syndrome quickly. Delivery, sometimes after a period of expectant management (“watchful waiting”), is a necessary intervention. Once the baby is delivered, mom still needs to receive care if she is experiencing high blood pressure and related preeclampsia symptoms.

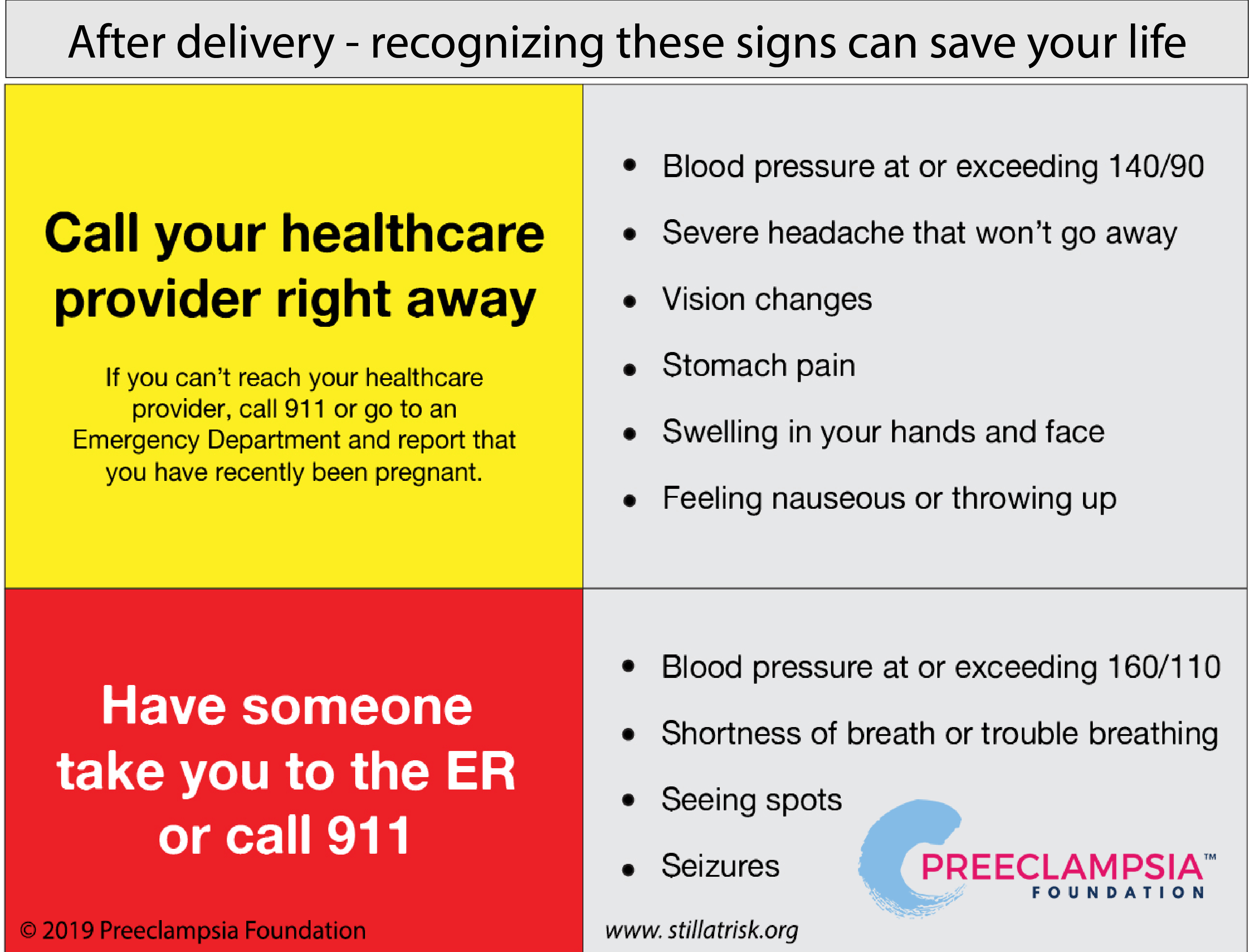

It's important to know that delivery is not the cure for preeclampsia. Any woman can develop preeclampsia after her baby is born, or postpartum preeclampsia, whether she experienced high blood pressure during her pregnancy or not. Moms need to continue to monitor their health after delivery. Recognizing these warning signs can save your life:

.png)

Still at Risk

Mothers at risk for postpartum preeclampsia can be given this flexible bracelet as a reminder to stay vigilant for symptoms and to keep an eye on their blood pressure, even after they go home. The bracelet also reminds health care providers who may see her during the postpartum period that she recently delivered and may still be at risk of developing postpartum preeclampsia or postpartum eclampsia. The act of putting the bracelet on a patient triggers an important conversation about symptoms to be aware of and to act upon. Click the image above to purchase the "Still At Risk" bracelets.

Postpartum Preeclampsia: Frequently Asked Questions

What is postpartum preeclampsia?

Postpartum preeclampsia is a serious condition related to high blood pressure.1 It can happen to any woman who just had a baby. It has most of the same features of preeclampsia or other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, without affecting the baby.

What causes postpartum preeclampsia?

There’s no definitive cause of preeclampsia. Delivery, in most cases, is the acute treatment, not a cure. “It takes time for the uterus to shed its lining after birth, so this process may be behind the delay that's sometimes seen in [postpartum preeclampsia] after delivery," says James N. Martin, MD, past president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and member of the Preeclampsia Foundation Medical Advisory Board. It's also possible this condition begins during pregnancy but doesn't show signs or symptoms until after the baby has arrived.

When does postpartum preeclampsia occur?

Postpartum preeclampsia occurs most commonly within the first seven days after delivery2, although you’re still at risk for postpartum preeclampsia up to six weeks after delivery.

Can you get postpartum preeclampsia without having preeclampsia during pregnancy?

Yes you can; in fact, you may be at an even higher risk if you did not have preeclampsia during your pregnancy.3

What are the risk factors associated with postpartum preeclampsia?

The risk factors for postpartum preeclampsia are very similar to those associated with preeclampsia during pregnancy however, any woman -- regardless of previous experience with blood pressure problems, weight, diet, or exercise -- is at risk.

What can I do to prevent or treat postpartum preeclampsia?

Learn the warning signs for preeclampsia and pay attention to your body so you can spot symptoms right away! Early diagnosis through recognition and proper response to symptoms is key. Prompt treatment saves lives. Sleep deprivation, postpartum depression, more attention on the newborn, and a lack of familiarity with normal postpartum experiences all contribute to more easily ignoring or missing indicators of a problem. The warning signs described in the infographic shown here are cause for concern and you should immediately seek medical attention if you experience any of them.

I’m experiencing symptoms. I called my healthcare provider but haven’t heard back.

Trust your instincts and ALWAYS seek medical care if you’re not feeling well or you feel something isn’t right. Go to Labor and Delivery (L&D) or the Emergency Department and tell them you recently delivered. Notify your obstetrician or midwife of your decision to seek medical help.

I went to the Emergency Room and was sent home and now I’m feeling worse. What should I do?

If you’re experiencing warning signs of postpartum preeclampsia, go back to the Emergency Department, request to be seen by an OB, and report that you’ve recently given birth. Notify your healthcare provider that you’re experiencing symptoms and are at the hospital. Trust your instincts; take a friend or loved one to advocate for you, if possible.

If you know you can report to L&D in the postpartum period, go directly there to expedite services. Not all hospitals are able to see patients in their L&D departments post-birth. For that reason, we suggest most women report to the Emergency Department.

Can I breastfeed if I was sent home after delivery on medication for high blood pressure?

Treatment of high blood pressure while breastfeeding requires agreement among the mother, obstetrician, and pediatrician. It’s critically important that the mother’s blood pressure be controlled, and the benefits of early breastfeeding are recognized and prioritized. From time to time, strongly held opinions may err on the side of “protecting the newborn” from exposure to medications. However, high blood pressure medications have no or minimal risk to the newborn.

The early postpartum period (up to seven days after delivery) is when women who experience preeclampsia are at highest risk -- much of this risk can be lessened with effective blood pressure control.

Are certain drugs preferred while breastfeeding?

In general, drugs – and often combinations of drugs – should be chosen for their effectiveness. Provider choices will largely be driven by their clinical experience. For severe hypertension, combinations of drugs with different mechanisms of action may be needed: 1) ß-blockers that effectively lower heart rate, 2) vasodilators that open small blood vessels, and 3) diuretics that help get rid of excess fluid through urination.

Specific drugs4:

Nifedipine has been used in pregnancy for reduction in contractions without apparent adverse effects on fetuses. It’s used in some practices to alleviate painful “nipple spasm” in breastfeeding women.5

Labetalol: Because of the low levels of labetalol in breast milk, amounts ingested by the infant are small and would not be expected to cause any adverse effects in full-term breastfed infants. No special precautions are required in most infants.6

Furosemide is a diuretic that works to decrease the circulating blood volume. Treatment is particularly important for women with life-threatening conditions such as pulmonary edema, heart failure, and very severe hypertension. Concerns have been raised that reduction in maternal blood volume might reduce the volume of breast milk. This concern is increased by the need in pregnancies where the baby may have delivered preterm and breastfeeding is challenging to establish. In response to these concerns, furosemide has been studied as an agent to suppress lactation – and there is no evidence to suggest it suppresses milk production.

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors are agents that open blood vessels to reduce pressure. They have special beneficial properties for women with diabetes or renal disease. There are many choices of these inhibitors, but studies have shown Enalapril use during breastfeeding may be most effective with minimal exposure to the baby.

Should I stay on magnesium sulfate after my baby has been delivered? If so, for how long?

Magnesium sulfate is started prior to delivery to reduce the risks of maternal seizures, eclampsia. Most protocols recommend continuation for 24 hours postpartum when the risk for seizures remains high. In some circumstances such as incomplete blood pressure control or a concerning clinical profile, treatment may exceed 24 hours. If a seizure occurs after delivery, it is referred to as postpartum eclampsia.

What should I eat after having my baby to maximize my health?

Nutrition after giving birth is critical to good health. Brigham & Women's Hospital offers this information about Postpartum Nutrition After Preeclampsia.

- 1Creanga, A. (2017). Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2011-2013. Obstetrics & Gynecology, Page 6.

- 2Al-Safi, Z. E. (2011). Delayed Postpartum Preeclampsia and Eclampsia. ACOG, 1102-1107.

- 3Bigelow, C. A. (2014). Risk Factors for New-Onset Late Postpartum Preeclampsia in Women Without a History of Preeclampsia. AJOG

- 4Hypertension in Pregnancy: The Management of Hypertensive Disorders During Pregnancy. (2010). NICE Clinical Guildlines, 11

- 5Hebert, M. (2005). Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Atenolol During Pregnancy and Postpartum. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 45: 25-33.

- 6LactMed: Drugs and Lactation Database. (n.d.). Retrieved from Toxnet: https://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/newtoxnet/lactmed.htm

Related Articles

Ánimo y cuídate: la preeclampsia puede estar asociada con enfermedades cardíacas y accidentes cerebrovasculares más adelante en la vida Descargue nuestra hoja informativa

Eclampsia is a very serious complication of preeclampsia characterized by one or more seizures during pregnancy or in the postpartum period.

La preeclampsia, en todas sus formas, puede requerir muchos análisis, tanto durante como después del embarazo. ¿Alguna vez se preguntó por qué el proveedor de atención médica le solicita tantos anális...

El embarazo es un momento ideal para familiarizarse con su presión arterial. Aquí encontrará todo lo que necesita saber sobre cómo tomarse la presión arterial en casa.

Melbourne, FL – October 7, 2025 – The Preeclampsia Foundation launched two new educational resources to help expectant moms and their providers better understand the growing field of predi...

Melbourne, FL – September 17 , 2024 – The Preeclampsia Foundation, in partnership with the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP) and Society for Ma...

Resultados de varios estudios apoyan la hipótesis de que el estrés causado por un embarazo y parto traumáticos puede en muchas ocasiones anular la habilidad de salir adelante emoc...

Is there a connection between maternal diet and preeclampsia? The PRECISE Network research team and I recently completed an evidence review to compile information on maternal nutritional factors that...

What you’ll learn in this article: Many risk factors contribute to an individual’s chance of getting preeclampsia. These risk factors may be genetic, physical, environmental, and even s...