How do you test for preeclampsia?

Last Updated on February 18, 2026

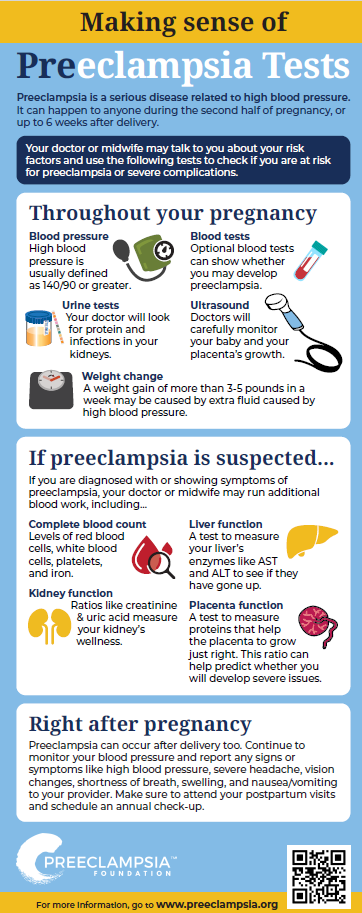

Making sense of preeclampsia tests

Preeclampsia, in all of its forms, can mean a lot of testing, both during and after pregnancy. Have you ever wondered why your healthcare provider is running so many tests? Or what those tests mean? This guide explains what tests may be done during and after pregnancy, when, and why.

DURING PREGNANCY

The first test for preeclampsia is to check your blood pressure at each prenatal checkup. When you become pregnant, you have regular visits with your provider. They should check your blood pressure at each visit to make sure it isn’t too high. A urine sample is also usually tested at each visit with a dipstick to make sure your kidneys are healthy. Any excess amount of protein found in a urine sample is known as "proteinuria." Protein in the urine may be a sign of preeclampsia, but is no longer required for a diagnosis. It is one factor that may signal an issue during pregnancy.

Preeclampsia can happen to any patient during or right after pregnancy. It can occur in any pregnancy, not only first-time pregnancies. A preeclampsia diagnosis requires two factors:

- Persistent high blood pressure that develops after 20 weeks or up to six weeks postpartum, AND

- signs of organ failure, such as

- High levels of protein in the urine,

- Decreased blood platelets,

- Signs of liver trouble,

- Fluid in the lungs, or

- Signs of brain trouble, like severe headache, seizure, and/or visual disturbances

Prenatal visits are scheduled closer together near the end of the pregnancy. At 32 weeks in an uncomplicated pregnancy, visits are usually every two weeks; at 36 weeks they become weekly. This is to help watch for sudden changes in you or your baby's health. Patients with higher risks are seen more frequently.

Learn more about preeclampsia's signs and symptoms

Blood pressure

Your healthcare provider should measure your blood pressure at each prenatal appointment. This should be done after you’ve been sitting comfortably for a few minutes, with the cuff on your upper bare arm at heart level, your arm and back supported, and your feet flat on the floor. Pressure can vary in different arms, so ask your caregivers to use the same arm every time. High blood pressure is traditionally defined as blood pressure of 140/90 or greater, measured on two separate occasions six hours apart. Severe high blood pressure, which is a reading at or greater than 160/110, requires treatment right away both during pregnancy and in the first weeks after delivery.

Learn how to take your blood pressure

Urine test (Urinalysis)

You provide urine at every prenatal appointment. Healthy kidneys don’t allow a significant amount of protein to pass into the urine. If protein is detected in your urine dipstick screening test, you may be asked to collect all of your urine in a jug for 12 or 24 hours to determine the amount of protein being lost. (Store the jug in the refrigerator or a cooler full of ice in your bathroom.) This urine will be tested to see if you are passing more than 300 mg of protein in a day. Any amount of protein in your urine over 300 mg in one day may indicate preeclampsia. However, the amount of protein doesn’t define how severe the preeclampsia is or may get.

Alternatively, your provider may do a "spot check" to immediately check levels of protein compared to creatinine, also an indicator of kidney health. A protein:creatinine ratio over 0.3 mg/dl is roughly the equivalent of 300 mg of proteinuria (or more) over 24 hours.

Blood tests

Women may have blood drawn and tested for a complete blood count (CBC) with platelet count and assessment of creatinine, liver enzyme levels, and sometimes uric acid. This blood work provides a baseline that your providers can monitor. Additional tests may also be ordered in a hospital setting to look at whether your placenta is healthy and doing its job. These tests can be used along with other lab tests and clinical assessments to help you and your provider to make educated care decisions about your treatment.

Most providers will draw blood again to compare and look for changes in your liver and platelets if you have symptoms of severe preeclampsia. In severe forms of preeclampsia (such as HELLP syndrome), your red blood cells can be damaged or destroyed to cause a type of anemia. This blood test may be called a “preeclampsia panel”, “HELLP workup”, or “PIH labs” by your providers. Your provider will look at whether your liver enzymes (AST and ALT) have gone up, and if your platelets have gone below the normal range of 150,000-400,000.

Weight

Most providers also routinely weigh you to assess whether your weight gain is within the normal range. Although swelling can be normal in pregnancy, swelling in your face and hands and sudden weight gain (five pounds or more in a week) sometimes precedes signs of preeclampsia. This sudden weight gain may signal that your body is holding onto excess fluid.

There are some first and second trimester tests being developed and clinically validated to assess a patient's risk for preeclampsia, especially severe or early-onset versions. Your provider may use such a test to add additional knowledge to their clinical judgment. Remember that no test currently exists to perfectly predict what patients will or won't develop preeclampsia. These tests are tools that providers use to more fully understand what is happening during your pregnancy. A high-risk result means there is an increased risk of developing preeclampsia in this pregnancy. It does not mean you will definitely develop preeclampsia.

Some terms you might hear related to different types of screening tests include...

sFLT-1 (soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1) and PLGF (placental growth factor): two proteins related to blood vessel development. sFLT-1 is an "anti-angiogenic protein," which means that it decreases the creation and growth of new blood vessels. PLF is a "pro angiogenic protein" which means that it promotes the development and growth of new blood vessels. Balance between these two proteins help to create and sustain a healthy placenta. In patients who develop preeclampsia, the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio can be elevated early in pregnancy, suggesting that the body is attempting to limit blood vessel formation, potentially contributing to complications like high blood pressure and organ damage. Two FDA-approved tests are also available in the US for use for hospitalized patients as a tool to assess whether a patient may go on to develop severe symptoms within two weeks.

PAPP-A (Pregnancy Associated Plasma Protein A): a protein produced by the placenta during pregnancy related to implantation and placental growth. A low level of PAPP-A during the first trimester is associated with pregnancy complications like preeclampsia, but it’s not very good by itself at predicting if you will get it. A low PAPP-A level can be a marker of higher risk, but it doesn’t mean you'll definitely get preeclampsia. Some high risk doctors may use this value in combination with other screening tools (like the sFLT-1/PLGF ratio and ultrasounds) to help assess risk.

AFP (alpha-fetoprotein): a plasma protein produced by the fetus related to fetal growth, that peaks around 15-20 weeks' gestation. High AFP suggests placental injury and a risk for Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR), which refers to a condition in which the baby is smaller than it should be for its gestational age. However, not all patients with high AFP may go on to have preeclampsia. There are many reasons that a pregnancy might experience high AFP and related IUGR.

RNA (ribonucleic acid): RNA drives tissue development during pregnancy by bringing important instructions to the cells of the mother, baby, and placenta. Messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a molecule that contains the instructions to tell cells how to make proteins. mRNA is made by “reading” deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), then is released into the cell where it tells the body’s amino acid how to make a specific protein. Once the mRNA is used, it breaks down and is released into a person’s blood stream. These broken-down products are called cell-free RNA. They are made up of several types of longer and shorter pieces of mRNA, miRNA (microRNA), and lncRNA (long non-coding RNA). A simple blood sample can show the presence of cell-free RNA, and how active certain genes have been based on their presence. By studying a collection of these RNA patterns, scientists can get a better picture to understand this pregnancy's unique risk factors.

What happens if I screen positive for being at-risk of preeclampsia? Patients who screen positively for being "at risk" of developing preeclampsia will likely be recommended to take low-dose aspirin, have more frequent monitoring, and address any chronic conditions like pre-existing high blood pressure, diabetes, or certain autoimmune conditions. Being "at risk" for preeclampsia is not a guarantee that you will develop preeclampsia. You and your provider can work together to shape a personalized pregnancy care plan that make sense for you. You can also learn about and report signs and symptoms sooner.

Learn more about the recommended "Care plan for individuals at risk of preeclampsia"

Monitoring of your babyOften signs (like abnormal lab values or high blood pressure) and symptoms (such as headache, swelling, vision issues, etc.) of preeclampsia mean that your baby may be more closely monitored as well. You may be scheduled for more frequent ultrasounds or non-stress tests (NST) to make sure the baby’s growth isn’t affected. They may also look to see that the blood flow through the umbilical cord and placenta is normal. If symptoms appear rapidly toward the end of your pregnancy or during delivery, you may receive continuous fetal monitoring in the hospital.

IMMEDIATE POSTPARTUM

Preeclampsia symptoms can also appear for the first time after delivery up to six weeks postpartum, sometimes even without having symptoms before the birth of your baby. You should tell your provider if you experience any symptoms such as a severe headache, visual changes, stomach pain, difficulty breathing or chest pain, or nausea. A medically complicated delivery may also require you to stay in the hospital for at least two or three days longer than normal, until the symptoms begin to go away and other indicators like blood pressure readings are trending toward normal (even if they aren’t normal yet).

Blood pressure changes can vary. In some patients, blood pressure may drop quickly, or be highest about three to six days after delivery, or take a few weeks to become normal. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that your blood pressure be checked three days and then 10 days after delivery – this can be done at home or in the hospital or healthcare provider's office. If your blood pressure is high three months after delivery, you should see a doctor who provides regular care for women who develop chronic hypertension (e.g., an internist, a maternal-fetal medicine subspecialist, or an OB/GYN specialist).

Many women choose to take their own blood pressure at home with a personal cuff, and to record the numbers in a chart for their providers to see. If you do this be sure to record the date and time of each reading. Remember, preeclampsia can appear up to six weeks after delivery even if you haven’t had symptoms during your pregnancy.

AFTER PREGNANCY

After pregnancy, you and your provider may decide to pursue additional tests to uncover underlying conditions that may have contributed to you developing preeclampsia.

Auto-immune conditions

Some women show symptoms of autoimmune conditions after delivery, where the woman's immune system responds to her own healthy cells as if they are threats. If you develop chronic symptoms like fever, tiredness, headache, swelling, aches, clammy skin, rashes, abrupt weight gain or loss, or if you develop a blood clot, follow up with your doctor and mention that your pregnancy history might be related to your symptoms. However, you can have these symptoms and a history of preeclampsia, and not have any autoimmune conditions.

If you develop autoimmune thyroid problems, they need to be treated. If you have symptoms such as a racing pulse or anxiety, your provider can run a thyroid panel blood test and analyze your numbers. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (also known as TSH) is a pituitary hormone that stimulates the thyroid gland to produce thyroxine (T4), and then triiodothyronine (T3) that stimulates the metabolism of almost every tissue in the body. After an evaluation of your symptoms, TSH levels, T3 and T4 balance, and presence of thyroid antibodies, you may need treatment.

Women with antiphospholipid antibodies, including women with lupus, are more likely to have recurrent pregnancy loss, develop blood clots when they’re not pregnant, and experience pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia. If your pregnancy history includes multiple miscarriages, miscarriages after 12 weeks of pregnancy, or preeclampsia before 34 weeks, you may be evaluated for lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, and beta 2 glycoprotein antibodies. You may be given blood thinners in any future pregnancies to lower your risk of developing a clot.

Blood clotting disorders

Women who have developed blood clots in their legs or lungs, and who have a history of preeclampsia, may be tested for hereditary blood clotting conditions like Factor V Leiden, PAI 4G/4G, or the MTHFR polymorphisms. Doctors vary in how they choose to treat women who test positive for any of these.

Kidney function

Your kidneys after preeclampsia will almost always take some time to heal, but they should go back to normal after delivery. Some women, especially those rare few who needed dialysis after delivery, may need several more tests to make sure their kidneys have healed. Kidney function is generally assessed by serum creatinine. Your creatinine levels might sometimes resolve, but not your proteinuria count. Your provider should check your kidney function until it returns to normal and your protein levels resolve. If your creatinine and proteinuria levels do not return to normal by six months, or if it gets worse, you should be seen by a kidney specialist (a nephrologist).

LONG-TERM CARE

Women who have had preeclampsia in pregnancy may be at higher risk of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, renal failure, clot formation, and chronic high blood pressure later in life. Talk to your doctor every year at your well-woman visit about your preeclampsia risk factor. Annual monitoring of your weight, blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol is an important way to stay healthy.

Heart health

The American Heart Association includes preeclampsia on its list of risk factors for heart disease and stroke. Evaluation for risk of later-life cardiovascular disease requires consideration by the provider and patient. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advises that women with a history of preeclampsia (who gave birth before 37 weeks of gestation) or who have a history of recurrent preeclampsia get a yearly assessment of blood pressure, lipids, fasting blood glucose, and body mass index.

Read more about how you can care for "My Health Beyond Pregnancy"