Centering Black, Indigenous, and Women of Color: 7 Keys to Confronting the Maternal Health Crisis

Recently, I came across a social media post calling attention to the global maternal health crisis from a Black woman’s perspective. Someone responded to the post asking, “What’s race got to do with it?” Others questioned why the campaign was focused on Black women instead of all women.

Recently, I came across a social media post calling attention to the global maternal health crisis from a Black woman’s perspective. Someone responded to the post asking, “What’s race got to do with it?” Others questioned why the campaign was focused on Black women instead of all women.

As a Black woman who has personally faced the challenges of preeclampsia and the US maternal health crisis, advocating for increased awareness and action to solve this issue has become my mission and professional calling. I couldn't help but wonder: Why isn't it obvious why Black women are being centered in this crucial public health issue? Are so many people still uninformed about this problem?

An All Too Familiar Headline

By now, we've likely all seen the media headlines of this tragic story: elite Olympic athlete Tori Bowie died alone while giving birth at 32 years old. According to the autopsy and news reports, the cause was complications during childbirth — possibly stemming from respiratory distress and eclampsia, a serious complication of high blood pressure during pregnancy that is characterized by seizures on top of high blood pressure and may lead to coma, brain damage, and even infant and maternal death. This often occurs in conjunction with signs and symptoms of preeclampsia, but may also appear without warning signs. Eclampsia can happen at any point before, during, or after childbirth.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the first time we’ve seen this headline or heard this story. In 2017, Dr. Shalon Irving, a brilliant public health scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), died weeks after giving birth to her daughter due to postpartum health complications. Her death sparked national attention around maternal morbidity and mortality among Black women in the U.S. and the health disparities that affect so many others. According to the CDC, severe maternal morbidity (SMM) is when a woman experiences unexpected complications during childbirth that result in significant short- or long-term effects on her health. It can increase the risk of maternal death and includes conditions like heart attack, respiratory distress, and sepsis. Other indicators include kidney failure and needing a blood transfusion. Globally, maternal mortality has been defined as maternal death occurring within 42 days of giving birth due to reasons directly related to the pregnancy rather than accidental causes. However the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System (PMSS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have expanded that definition as a pregnancy-related death as a death while pregnant or within one year of the end of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy.

That same year, I narrowly escaped a similar fate at only 28 weeks pregnant with my son Jaxson. Tragically, I experienced a placental abruption from preeclampsia that caused him to be stillborn. Although this was a high-risk pregnancy, I am certain with the proper care and attentive response to my healthcare concerns, my abruption and my son’s death could have been prevented.

Despite my shock and frustration at the lack of public understanding of the US maternal health crisis, the answer to their question “what’s race got to do with it?” lies in my story. Despite being a successful, highly educated clinical social worker, I faced bias and discrimination from the healthcare system. I was sent home from the emergency department multiple times, despite having extremely concerning blood pressure readings. Like many others we read about in the headlines, I, too, was not immune.

Why a Focus on Race

As I continued scrolling through the comments on this social media post, it became clear that it had become a heated discussion about race. The original message of the post was to shed light on a Black mother's struggles with maternal health complications. But that seemed lost in a sea of offensive remarks, stereotypes, and judgmental opinions. Some argued whether the conversation around maternity care should focus on Black women.

In contrast, others questioned if framing it as a racial issue would only create more division and exclusion. Meanwhile, some respectfully asked for more information about the underlying factors contributing to these inequalities.

More research studies are attempting to answer these important questions. For example, a study published in the American Journal of Hypertension, of over 4,000 births in Chicago, found that living in highly segregated neighborhoods with high levels of poverty was associated with a higher likelihood of developing hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. This research highlights the need to address sources of disparities such as structural racism associated with adverse maternal health outcomes. Recent studies like this one published in the Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health and this one published in 2012 in the Annals of Behavioral Medicine have also shown that stress from racism can impact infant birth weight in Black mothers compared to white mothers, further contributing to disparities in outcomes.

According to research by the CDC, more than 80% of maternal deaths are preventable, yet Black and Indigenous mothers continue to experience poorer outcomes compared to other races. So, when asked, “what does race have to do with it?”, we can begin with the facts:

- Black women are 2-3 times more likely to die in childbirth compared to women of other races (Centers for Disease Control, 2023)

- Preeclampsia affects 5-8% of pregnancies in the U.S., with Black women being 60% more likely to develop preeclampsia (Preeclampsia Foundation, 2020).

- Among Indigenous women, including those who identify as American Indian or Alaska Native, pregnancy-related deaths also occur at higher rates. Mental health issues and hemorrhage are identified as the primary causes in 50% of these cases (Trost et.al, 2022)

The healthcare needs of Black, Indigenous, and Women of Color (BIWoC) are historically understudied, leading to gaps in research and medical knowledge. Therefore, it’s crucial to center race in our analysis of the maternal health crisis for numerous reasons, including improving maternal health outcomes for BIWoC in the United States and globally.

Focusing on the experiences of BIWOC (Black, Indigenous, and Women of Color) communities allows us to gain a deeper understanding of the changes needed within our systems to benefit all individuals. This approach ensures that no one is left behind. In her article "The Curb-Cut Effect”, Angela Glover Blackwell emphasizes the significance of placing the needs of the most marginalized at the forefront for overall societal progress:

“There’s an ingrained societal suspicion that intentionally supporting one group hurts another. That equity is a zero-sum game. In fact, when the nation targets support where it is needed most — when we create the circumstances that allow those who have been left behind to participate and contribute fully — everyone wins. The corollary is also true: When we ignore the challenges faced by the most vulnerable among us, those challenges, magnified many times over, become a drag on economic growth, prosperity, and national well-being.”

These stories illustrate how BIWoC must navigate a system that carelessly neglects them during one of the most vulnerable times in their lives. Implicit biases, systemic racism, and barriers to healthcare only further exacerbate the already inadequate treatment they receive. Medical professionals pledge to uphold the Hippocratic Oath and adhere to a code of ethics that prioritizes doing no harm to patients. This should not have to be enforced; it should be a moral obligation. The fact that many BIWoC are still battling over birth in the wealthiest nation in the world only exposes the hollowness of these commitments. We must confront the role that race, racism, and bias play in shaping their birthing experiences. Anything less would be a betrayal to those mothers who deserve nothing but the best care for themselves and their children.

How do we elevate BIWoC voices to improve the US maternal health crisis?

No matter your relationship to this problem, whether you are a BIWoC mother who has personally experienced maternal health complications, a healthcare provider committed to ending the Black maternal health crisis, or an advocate, family member, or friend, I urge you to join us in finding solutions. This is your call to action!

Here are seven key ways that you can amplify the voices of Black mothers in the fight for birth justice and healthcare reform:

- Bring to light their unique stories

In the wise words of Maya Angelou, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” For BIWoC, this agony is all too common, as our stories are often silenced or overlooked. Being pushed to the sidelines leads to a lack of diversity and representation in maternal health. As a result, it’s more difficult to address the critical needs of certain groups with the urgency they deserve. It’s necessary to highlight diverse voices. Sharing our stories shifts power, promotes healing, provides real life examples that can be instructive, all helping us confront this tragic epidemic. One way that the Preeclampsia Foundation is doing this is through their Gathering Table events, which bring together BIWoC women in communities across the US to talk about their maternal health experiences and amplify their voices. Another way is to join the MoMMAs Voices Patient Family Partner certification program (https://www.mommasvoices.org/moms-families) to get trained on how to use your lived experience to participate in maternal health quality improvement.

- Break the silence and stigma for BIWoC

The Preeclampsia Foundation's Take 10 Campaign is a crucial movement to ensure that Black women are included in research, urgently shedding light on the untold stories of Black women affected by the grave maternal health crisis, specifically surviving preeclampsia, and ensuring their stories and data are included in important and trusted scientific and medical investigations. Prioritizing race and historically neglected communities in research can promote equity and anti-racist interventions. Inspired and driven by this initiative, I have proudly taken on the role of a Take 10 ambassador and have poured my heart into writing this blog post. Breaking through barriers of silence and shame, I am bravely sharing my own story in hopes of helping others who may be suffering alone. It’s only through amplifying diverse voices on maternal health issues that we can demand much-needed change and let others know they are neither alone nor to blame for their struggles.

- Stop blaming BIWoC mothers

Instead of blaming BIWoC communities for having poorer health outcomes, we need to focus on the systems and policies that contribute to inequity. This includes addressing race as a crucial factor in accurately analyzing data and finding solutions for larger issues.

Associate professor Monica McLemore, a preeminent scholar of antiracist birth equity research, and Valentina D'Efilppo, an award-winning designer, creative director, and co-author, emphasize this in their joint article. They call for a shift from blaming women to understanding the multiple factors at play. Similarly, a study in Alabama found that racism, unjust laws, poverty, and inadequate infrastructure contribute to poor birthing outcomes for Black women. Therefore, change must occur at all levels (individual, familial, community-based, institutional, governmental, and societal) to address disparities and reform our healthcare system.

- Focus on root causes to find real solutions

The disproportionate number of Black mothers dying during childbirth is not due to their skin color but rather systemic bias. A study by Yale researchers found that pregnancy stigma based on race affects access to healthcare and support for Black women. Dr. Joia Crear-Perry, founder of the National Birth Equity Collaborative (now known as RH Impact), suggests addressing racism as a "modifiable factor" and says failing to acknowledge and address racism only perpetuates the issue and puts more mothers at risk. Implementing anti-bias training for healthcare providers and following best practices have been shown to improve maternal health outcomes for Black women.

- Advocate for racial equity within our healthcare systems

To improve healthcare for all women, we must prioritize health and racial equity in research, policymaking, and healthcare practices. Health equity means fair opportunity for everyone to achieve their best health without disadvantages based on race or societal constructs. Research shows that pregnant people of color face neglect and discrimination in healthcare. Racial concordance, improved communication, and culturally competent care can help address this issue and improve mother and baby outcomes. Everyone benefits when a community supports racial equity, fostering equal opportunities for success. One way we can support racial equity is by consciously applying a racial equity perspective to all aspects of our work and research, particularly those that may affect communities that have traditionally been excluded from discussions. For example, it's important to consider how different groups may be affected by our decisions, policies, or changes and to actively seek out the perspectives of those who have historically been left out of the conversation.

- Allocate funding and research that centers the needs of BIWoC

Mothers of marginalized identities are often not well represented in research studies or clinical trials. We must prioritize investing in understanding their unique needs and allocating resources, such as grant awards for projects focused on underrepresented communities. The National Institutes of Health’s IMPROVE initiative, launched in 2019 and received a budget of $43.4 million in fiscal year 2023, aims to combat high rates of maternal mortality and address disparities faced by minority, young, older, and disabled mothers. We must advocate for and fund projects like this to create the infrastructure for meaningful change.

- Advocate for social change that impacts mothers everywhere

In a bold move, the Biden-Harris administration declared April 11-17 as Black Maternal Health Week, highlighting the need for policy reform and addressing institutional racism. Vice President Kamala Harris has spearheaded efforts, securing funding from Congress to implement the Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis. The introduction of the Black Maternal Health Caucus' Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2020, which includes 13 individual bills and is endorsed by more than 200 organizations, has brought even more significance to the need for federal legislation and policy changes. Revamping a broken system that continually fails our mothers and babies, who in many cases identify as Black and brown, is overdue. These are examples of how creating social change starts by raising awareness, addressing policy deficiencies, and shifting cultural attitudes and deep-seated practices.

Your Call to Action

Act now. The time for change is long overdue. Women deserve to feel safe and supported during the sacred experience of bringing new life into this world, regardless of their race. If you are reading this and questioning why race matters in maternal health, I challenge you to consider your cognitive bias and how it may be contributing to the problem.

Real change starts with those in positions of power — the professionals responsible for our care and creating policies that shape our lives. It requires actively confronting implicit bias, breaking down harmful stereotypes, and demanding higher standards in healthcare practices. We must eradicate the deeply ingrained four levels of racism: personal, interpersonal, institutional, and structural — replacing them with anti-racist approaches, such as promoting patient-centered care that is culturally responsive to the needs of the communities served and engaging BIWoC in shared decision-making processes about their healthcare needs. We are not simply asking for birth equity. We demand justice for all. Will you join us in this fight?

Shakima “Kima” Tozay is a maternal health advocate and mother to her son, Jaxson, who was stillborn at 28 weeks due to preeclampsia. As a writer, speaker, Licensed Clinical Social Worker, U.S. Navy Veteran, and military spouse, Kima devotes herself to raising awareness of health inequities in maternal healthcare. She is a Certified Patient Family Partner with MoMMAs Voices, Mom Congress member, and serves on the Patient Advisory Council (PAC) through the Preeclampsia Foundation. Kima also shares her story through various advocacy platforms. When not volunteering, she enjoys exploring nature, road trips, and finds comfort in writing her son's name in the sand along the rocky beaches of Washington.

This article is for educational purposes. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the guest author and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any entities they represent.

Related Articles

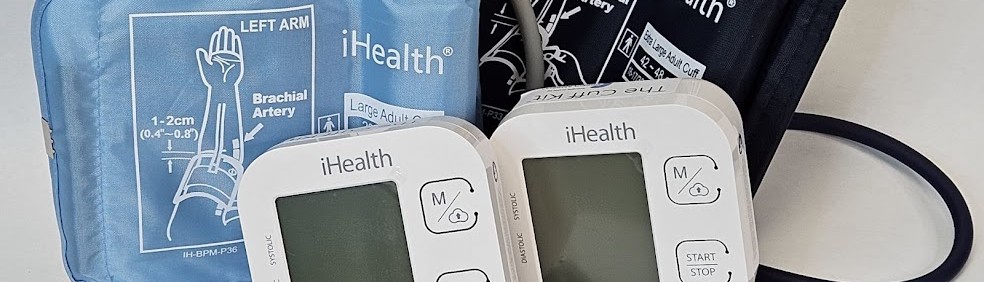

Congratulations on receiving your brand new Cuff Kit®! Want to learn more about how to use your iHealth Track device? Here are some handy videos and links to get you started. Unpacking and using...

A visual approach to understand preeclampsia patient experiences from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine & Preeclampsia Foundation

Nurses play a vital role in detecting preeclampsia and caring for patient before, during, and beyond pregnancy.

Doulas can help bridge the gap for any mom, but especially those most vulnerable to maternal illness and death.

A key component needed in the fight against preeclampsia is the development of tests for simple, rapid, and accurate diagnosis and prediction through the development and adoption of biomarkers.

Preventing and managing high blood pressure with healthy lifestyle behaviors are at the center of updated clinical guidelines published this week in the American Heart Association (AHA) peer-reviewed...

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are a leading cause of maternal death in the state of Indiana. To address this critical issue, the Indiana Hospital Association is teaming up with the Preeclampsia...

Recientemente, me encontré con una publicación en las redes sociales señalando la crisis de salud maternal desde la perspectiva de una mujer negra. Una persona respondió a...

For more on the Preeclampsia Foundation's work to amplify all research related to biomarkers for improved prediction and diagnostic tools, please visit https://preeclampsia.org/biomarkers. INDIANAPOL...

GAP—SPIRIN campaign gets low-dose aspirin to those most at risk to help close the maternal health gap in preeclampsia ________ NEW YORK, January 23, 2025/PRNewswire/ – In recognition of...